A Complete Guide To All Of The Grateful Dead’s Lineup Changes – Grunge

For 30 years, the Grateful Dead cultivated a legacy that went far beyond the musical world. They first came to public attention in the mid-1960s as part of the hippie movement burgeoning in San Francisco, California. They were originally known as the Warlocks before changing their name, and by the 1970s they started to taste commercial success outside of the confines of their psychedelic upbringing. Throughout the ’70s and ’80s, the Dead continued to release albums and tour consistently, finally calling it quits in 1995 following the death of co-founder Jerry Garcia.

While massive commercial success largely eluded the Dead during their career, they made their bones as one of the most intriguing and engaging musical acts in rock and roll history. They also spawned the Deadheads, a community of fans so devoted to the band that they would follow them around from show-to-show — sometimes for years on end — and eventually created a small traveling community with a family-like atmosphere.

Throughout it all, the Dead constantly underwent lineup changes that would force them to keep developing and refining their sound. They had an inconstant cast of characters, which included no fewer than six keyboard/piano players, but they always found a way to keep going. This is the complete guide to all of the Grateful Dead’s lineup changes.

1965–1967: The original Warlocks

Leni Sinclair/Getty Images

Leni Sinclair/Getty Images

The humble beginnings of the Grateful Dead started back in 1965, at the height of the hippie and psychedelic era. In late 1964, guitarists Jerry Garcia and Bob Weir, as well as keyboardist Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, were playing together in a folk band known as Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions. However, prompted by Pigpen, the band started to consider switching from unplugged folk music to electrified blues.

They soon hooked up with drummer Bill Kreutzmann, and Mother McCree’s quickly fell by the wayside. The first official concert of the new electrified blues band took place on May 5, 1965, at a pizza parlor, and the band went by the name of the Warlocks. The group consisted of Garcia, Weir, Pigpen, and Kreutzmann, with Dana Morgan on the bass. However, Morgan’s days with the band were numbered.

Due partly to his National Guard commitments, as well as his wife’s distaste for the band, the guys looked to replace Morgan from the very beginning. After seeing a performance of the Warlocks at the pizza parlor under the influence of LSD, Phil Lesh talked with his old friend Garcia about joining the band, and on June 18, the Grateful Dead’s core lineup played their first show together with Lesh on bass instead of Morgan. A few months later, that November, the band changed their name, and the Grateful Dead was born.

1967–1968: Mickey Hart becomes the 2nd drummer

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

By the fall of 1967, the Grateful Dead were starting to hit their stride. Fresh off the release of their self-titled debut album that March, the Dead were starting to break out of their shell and taste more success. That September, they played a pair of gigs at the Straight Theater near their house, which — in order to get around the strict rules requiring dance permits — were billed as “dance lessons” rather than rock shows (via Dennis McNally’s official band biography “A Long Strange Trip”). While already a bit quirky, in hindsight, these shows are actually some of the most important in Dead history.

It was during the second night on September 30, 1967, that Mickey Hart first sat in with the band. The band already had a drummer at that point, Bill Kreutzmann, but adding a second percussionist was actually his idea. Hart sat in and played with the band during the second set of the evening, and things immediately took off. A lifelong drummer with rhythm in his blood, Hart was a perfect fit for the Dead both musically and spiritually.

After joining the band officially, Hart and Kreutzmann began to work on synchronizing their drumming. They moved in together, and soon began esoteric rituals like attempting to harmonize their heartbeats and pulses to become as integrated as possible. The pairing worked well, and now the Dead had a new member.

1968–1970: Tom Constanten brings the psychedelia

Steve Snowden/Getty Images

Steve Snowden/Getty Images

Though his time in the band was relatively short-lived, Tom “TC” Constanten provided one of the most unique voices in the history of the Grateful Dead. His entrance into the band was predicated on his longtime friendship with bass player Phil Lesh. Lesh and TC had originally met in 1961 at the University of California Berkeley. They quickly hit it off, and within a year they were living with each other in Las Vegas.

Fast forward six years, and Constanten and Lesh were once again in each other’s company, this time in the capacity of the Dead. The band was seriously delving into their psychedelic period, and things were getting increasingly stranger. Luckily, Constanten fit right in. Claiming he was recruited due to his “bizarre avant-garde stuff,” Constanten would resort to peculiar and inventive tactics with his piano to find the most extraordinary and ludicrous sounds possible (via David Browne’s “So Many Roads: The Life and Times of the Grateful Dead”).

He was brought in to help with what would eventually become the 1968 album “Anthem of the Sun,” and was actually still in the Air Force when he began recording with them. He would eventually become the band’s full-time organist/keyboardist, and also appeared on the subsequent albums “Aoxomoxoa” and the live album “Live/Dead,” both released in 1969. However, change was once again on the horizon.

1970–1971: Constanten departs after the bust

Kypros/Getty Images

Kypros/Getty Images

The year 1970 was one of the most productive in Grateful Dead history. That year, they released two albums, “Workingman’s Dead” and “American Beauty,” which would spawn some of the most memorable hits of their career. “Workingman’s Dead” had longtime favorites like “Uncle John’s Band” and “Casey Jones.” Meanwhile, “American Beauty” would have concert staples like “Sugar Magnolia,” “Friend of the Devil,” and “Truckin’.”

However, the period was markedly different than the one prior, somewhat due to the departure of former organist and keyboardist Tom “TC” Constanten that January. Constanten’s exit from the band coincided with a drug bust in New Orleans, but it had been clear for a while that he and the band were not the best of fits. While his musical contributions were always highly valued, personality-wise he was often at odds with the band’s ethos.

According to “A Long Strange Trip,” Constanten’s stances on both religion — he practiced scientology — and his abstinence from psychedelic drugs like LSD, kept him spiritually apart from much of the band and their crew. He ended up leaving to pursue a career in composing, and the band never looked back. The Dead played as a five-piece without him for the next year, and in 1971 they released their second self-titled album, affectionately known by Deadheads as “Skull & Roses” due to the cover image. However, by then Constanten wouldn’t be the only member to have left the band.

Hart’s turn to depart

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

When Mickey Hart joined the Grateful Dead, it turned out he wasn’t the only Hart who would eventually become involved with the band. Mickey originally joined the group in September 1967, but it wasn’t until April of 1969 that his father, Lenny Hart, would also find his way into the Dead’s fold. As told in “A Long Strange Trip,” the band turned to Lenny as their new manager in an effort to turn around their dismal financial position. Though Lenny was enthusiastic, other members of the Dead’s entourage, which included famous promoter Bill Graham, were less sure of his honesty.

It turned out that the doubters were right, and over roughly a year Lenny embezzled more than $150,000 of the band’s money behind their backs. He was kicked to the curb and fled to Mexico, and Mickey was shattered by the betrayal. It had been Mickey’s idea to introduce his father as manager in the first place, and it became almost overwhelming for him when he left. Lenny wouldn’t be found until July of the next year, and though he would be sentenced to jail time, the band only got back a fraction of what he took.

Mickey stayed in the band for the completion of “Workingman’s Dead” and “American Beauty,” but he departed in February 1971. Much of the reason for his separation was likely linked to his father’s duplicity, which hurt him to his core.

1971–1972: Keith Godchaux enters the picture

Larry Hulst/Getty Images

Larry Hulst/Getty Images

In October of 1971, the Grateful Dead released their second live album, which was self-titled but is widely called “Skull & Roses.” While it was a good showcase of the band’s live repertoire up to that point, Deadheads who bought the album and went to see the Dead in concert would be in for a bit of a surprise. That same month, pianist and keyboard player Keith Godchaux officially joined the band.

Godchaux debuted with the Dead on October 19, 1971, at the Northrop Auditorium at the University of Minnesota. The band played a number of new songs that night, including later concert staples like “Jack Straw,” “One More Saturday Night,” and “Tennessee Jed.”

According to Sean Piccoli’s “The Grateful Dead,” Godchaux joined the band after introducing himself to Jerry Garcia following a gig one night. By the weekend they were jamming, and soon Godchaux was joining them onstage behind the piano. Part of the reason they hired Godchaux was due to the declining health of Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, who was the band’s current organ and keyboard player in addition to pulling duties as frontman.

1972: Pigpen’s last shows with the Dead

Larry Hulst/Getty Images

Larry Hulst/Getty Images

On March 8, 1973, tragedy struck the Grateful Dead. That day, beloved frontman and organist Ron “Pigpen” McKernan was found dead at the age of just 27 years old. The cause of death was internal bleeding linked to liver damage from years of heavy alcohol use. He had started to miss concerts a few years earlier due to his illness, and eventually he became so sick that he had to stop touring with the band altogether. His funeral, held four days later, was well attended by both hippies and bikers (via Rolling Stone).

As longtime roadie Steve Parish recalled in “Home Before Daylight: My Life on the Road with the Grateful Dead,” as McKernan’s health disintegrated the band was not always aware of what was going on. They knew that he was sick enough to be missing shows, but none of them understood that he was literally dying from his illness.

McKernan’s final show with the band was on June 17, 1972, at the Hollywood Bowl in California, and he was unable to perform any vocals. His health had completely deteriorated, and by the end of 1972 he was only a shell of his former self. His death three months later in March was hard on the band, but they nevertheless soldiered on and continued to play concerts.

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA’s National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

1972–1974: The last shows before hiatus

Electrascope

Electrascope

Following the death of longtime frontman and organist Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, the band continued on with Keith Godchaux taking over on organ and piano. At the end of 1973, the band released “Wake of the Flood,” which featured Keith and his wife Donna Jean Godchaux. Donna Jean had started singing with the band the year prior, after Keith had a chance to get settled in on piano. The following summer, the band released “From the Mars Hotel,” which again had both of the Godchauxes on it.

However, as 1973 turned into 1974 and the year progressed, cracks began to show in the Dead’s foundation. Toward the end of 1974, the band embarked on their second tour of Europe, but it was plagued with substance abuse issues and was largely unfulfilling both financially and personally (via “A Long Strange Trip”).

That October, the band decided to play a final week of shows at the Winterland Arena in San Francisco, California, before officially retiring. No one for sure knew if the Dead was ever going to return again, and the concerts were filmed for posterity, eventually being released as “The Grateful Dead Movie” a few years later.

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA’s National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

1974–1979: Hart rejoins the Dead

Larry Hulst/Getty Images

Larry Hulst/Getty Images

While the band was celebrating their possible end during the Winterland shows of October 1974, in a way, it was also a new beginning. On the final night, October 20, Mickey Hart rejoined the Grateful Dead after two and a half years away. After being informed about the shows, Hart brought his gear to the arena and ended up playing the second set with them. Just like that, he was back in the band.

With the Dead supposedly retiring, it was unclear what the future held for the band. But their retirement was very short-lived, and soon they reconvened at guitarist Bob Weir’s house and began jamming again in a laid-back environment without expectations. These jam sessions culminated in the album “Blues for Allah,” which was released in September of 1975. The name was dedicated to the Saudi Arabian King Faisal, who had died earlier in the year.

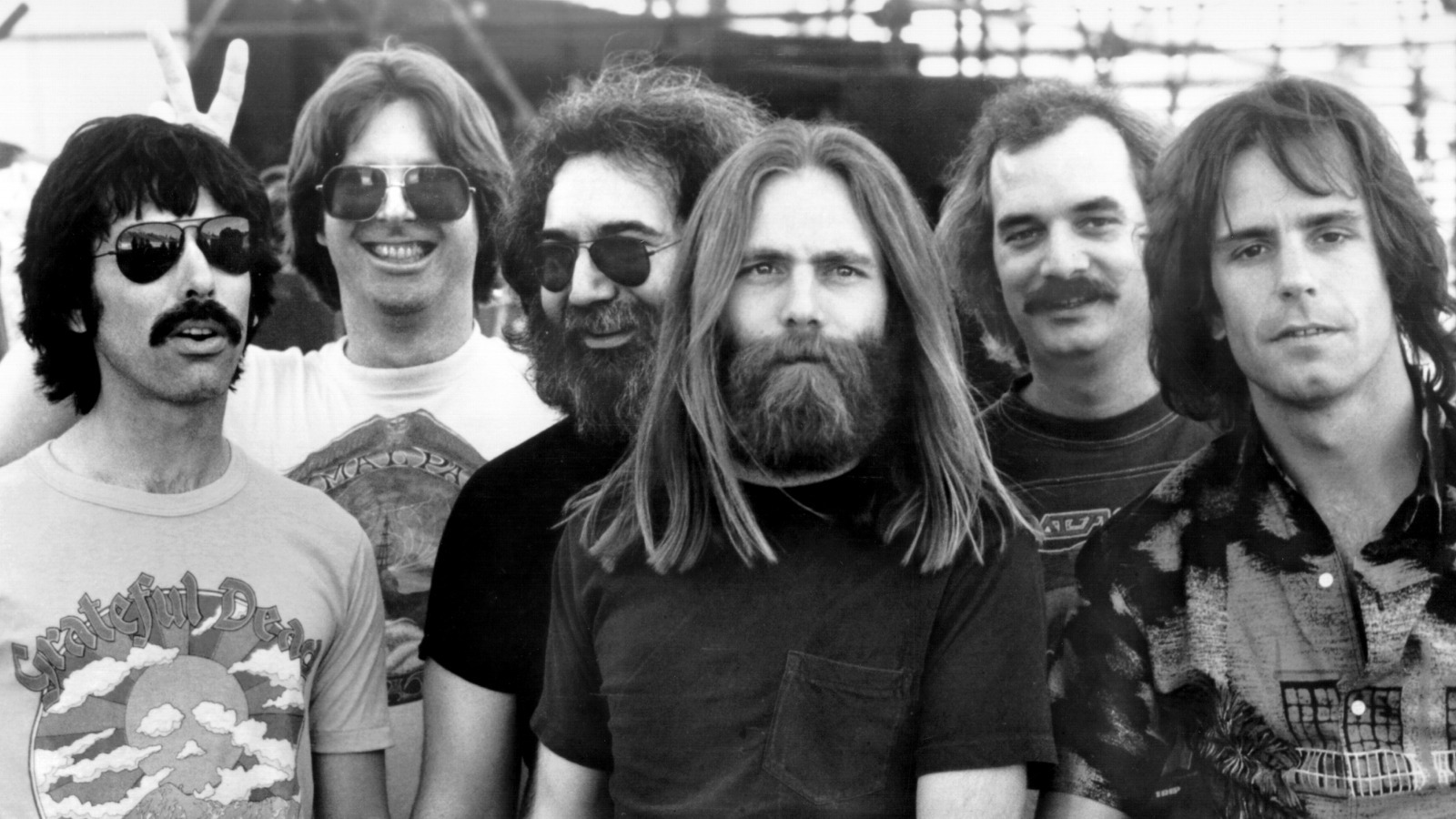

The band was now a seven-piece, which would be their biggest lineup. Jerry Garcia (above left) and Weir (above right) were on guitar, Phil Lesh was on bass, Bill Kreutzmann and Hart were on the drums, and husband and wife Keith and Donna Jean Godchaux were both performing. The band released “Terrapin Station” in 1977 and the disco-themed “Shakedown Street” in 1978, the latter of which would prove to be the last Dead studio album to feature a Godchaux.

1979–1990: Brent Mydland becomes the new guy

Tim Mosenfelder/Getty Images

Tim Mosenfelder/Getty Images

While the Grateful Dead had returned from their brief hiatus as strong as ever and still putting out great music, a rift was developing within the band. While the Dead had always been known for their partying ways, Keith Godchaux’s substance issues and tumultuous marriage to his wife Donna Jean started to take too much of a toll. In addition to their constant fighting, which would even rear its head when the couple was performing onstage, Keith’s playing started to suffer. In early 1979, Keith was let go from the band along with Donna Jean, with their last concert being a benefit on February 17 at the Oakland Coliseum Arena.

The band needed a new keyboard player, and Brent Mydland soon stepped up to fill Keith’s shoes. After a previous stop in Bob Weir’s band, Mydland got called up to the big leagues to play with the Dead, where he would stay for the next 11 years as their longest-tenured keyboard player.

He played his first show with the band on April 22, 1979, at the Spartan Stadium at Michigan State University. Mydland would last all the way until 1990, when fate would intervene once again to rob the Dead of another fantastic keyboard player.

1990–1995: Vince Welnick and Bruce Hornsby oversee the final years

Larry Hulst/Getty Images

Larry Hulst/Getty Images

At the age of just 37 years old, Brent Mydland passed away while in his prime playing with the Grateful Dead. He died on July 26, 1990, after overdosing on a combination of morphine and cocaine. His final show was on July 23, 1990. The Dead ended their performance that night with a cover of “The Weight” by the Band, and the last verse Mydland sang with the Grateful Dead was eerily “I gotta go, but my friends can stick around.”

The Dead wasted little time in replacing him, and less than three months later they were back on the road again. The band opted to bring in two organists/keyboardists to take over Mydland’s duties. The first to debut was Vince Welnick, who played his first show on September 7, 1990, at Richfield Coliseum near Cleveland. A week later, on September 15, Bruce Hornsby played his first show with the Dead at Madison Square Garden in New York City.

The band continued for the next five years, until the death of Jerry Garcia (pictured) in August of 1995 at a drug rehabilitation center. Garcia’s death effectively ended the Grateful Dead as a band, but it was not the final chapter in their history.

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA’s National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

The post-Grateful Dead reunions

Tim Mosenfelder/Getty Images

Tim Mosenfelder/Getty Images

With the death of Jerry Garcia in 1995, the band decided to retire the name Grateful Dead from touring. However, in the years since, the remaining members have found themselves onstage with one another quite often. The Furthur Festival in 1996 was set up by Mickey Hart and Bob Weir (above left) and was the first post-Garcia iteration. In 1998, the band, including Hart, Weir, Phil Lesh (above right), and Bruce Hornsby, reunited under the moniker of the Other Ones, which was based on the classic Dead song of the same name.

The band reunited again in 2000 under the same banner of the Other Ones, but this time drummer Bill Kreutzmann was there and Lesh was not. However, both were there for the next iteration in 2002. The next two years saw the band reunite as the Dead for successive summer tours. In 2008, Hart, Lesh, and Weir reunited again under the moniker of Deadheads for Obama, playing a benefit for then-presidential candidate Barack Obama.

Their final official reunion came over July Fourth weekend in 2015, when the band played a three-night blowout billed as “Fare Thee Well,” the name taken from their classic track “Brokedown Palace.” All living members, including Hart, Weir, Lesh, Kreutzmann, and Hornsby, were there, and it was billed as the official end of the Grateful Dead — though nobody knows what the future truly holds.